This Is Not A

BLOG!

This Is Not A

BLOG!

Date: 20/12/10

One Hundred Years

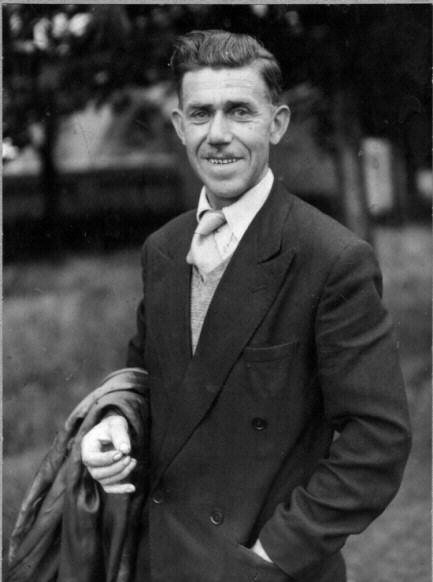

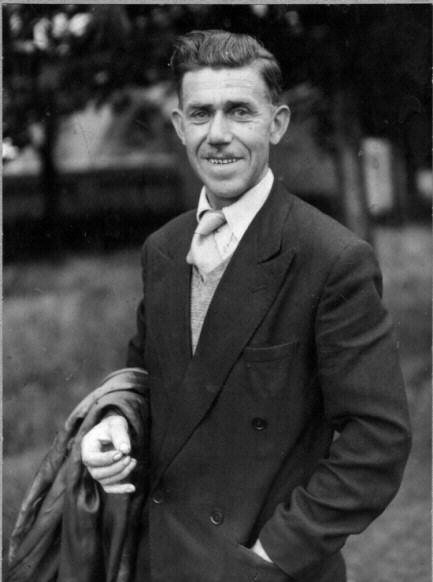

My father, William Alfred Stapley, would have been one hundred years old today.

He isn't, of course. He didn't get all that near it, dying a few days after his seventy-eighth birthday. But as my own lifetime goes on, I find myself thinking more about his life, and how he shaped me.

He was born at Mount Zion, a farm on the outskirts of Brymbo, shown on this picture.

(He was once asked by some supercilious prat of an official for his place of birth. My father, being a bit of a gamester, truthfully said "Mount Zion". To which the official told him to go back to his own country. This is funny, because Dad didn't look Jewish.)

He was the second child - and eldest son - of Harry and Mary Stapley, who lived in a terraced house at nearby Rhos Y Coed, and who went on to have eleven children.

Dad was raised at Rhos Y Coed, and at the age of fifteen went to work in Brymbo Steelworks as his father had done before him. The family then moved into a three-bedroomed house on the then-new Penygraig estate, where my grandmother lived until nearly the end of her days some fifty years later. Indeed, through one of those quirks of fate, it's the house I'm sitting in as I type this, the tenancy having - with a small gap - gone through three generations of the family.

Dad didn't work just at the steelworks during this time: he would also do seasonal work on farms around and about, including up the Vale of Clwyd as far as Ruthin. It was here that he learned the smattering of Welsh which he handed on to me as an unwitting preparation for my own learning of the language. Moreover, the steelworks itself closed completely during The Great Depression, forcing him to seek employment elsewhere. He re-trained as a pipe fitter and spent a couple of years or so working at British Celanese in Hertfordshire, where he also developed a sideline in being an amateur entertainer. He used to tell us of the times he'd performed in what was called a 'minstrel troupe' during that period.

He was also a useful sportsman - football and cricket for preference. He played football for the Brymbo Green club, and cricket for the village XI. Two anecdotes I recall from his days on the field:

- He was team captain, and had been displeased with the performance of the batsmen in the previous game. So, when the batting order went up on the board for the next game, they found that Dad had completely reversed it, putting the tail-enders in first. Poor Donny Ruddy - a real 'rabbit' in cricketing parlance - was reduced to a nervous wreck even by the prospect of opening the batting.

- He was once fielding square of the stumps (on-side or off-, I forget which), when the ball came quickly along the ground just to one side of him. The batsmen - seeing that Stapley, W.A. had turned his back, seemingly to watch the ball trundle to the boundary, set off for an easy run or two. Only to find that Dad had foxed them; he'd picked the ball up first time, waited for the batsmen to set off, then threw the stumps down. He claimed (and why should I disbelive him?) that he had been nick-named "The fastest hands and feet in North Wales" for this and similar feats.

I still have his old cricket bat here. It's bound in tape, but it's still as solid as when last he used it in the Forties.

He'd had other adventures as a young man. He once drove a car back from Ruthin - presumably in the days before you needed a licence - which didn't have a steering wheel. He steered the machine with a Stilson wrench. When you consider that the notorious Nant Y Garth Pass lies between Ruthin and here, and bear in mind what it must have been like seventy-odd years ago, you wonder at how close he came to grief.

On another occasion he did, crashing his motorbike into a post-box partly hidden by a hedge. This led to serious injuries, including losing most of his teeth and becoming permanently deaf in one ear. He claims that, while he lay there in hospital, he wrote on the chart:

"Here lies the body of William John (*);

His bike stopped, but he went on."

(*) His middle name wasn't John, it was Alfred, but you trying finding a rhyme for that.

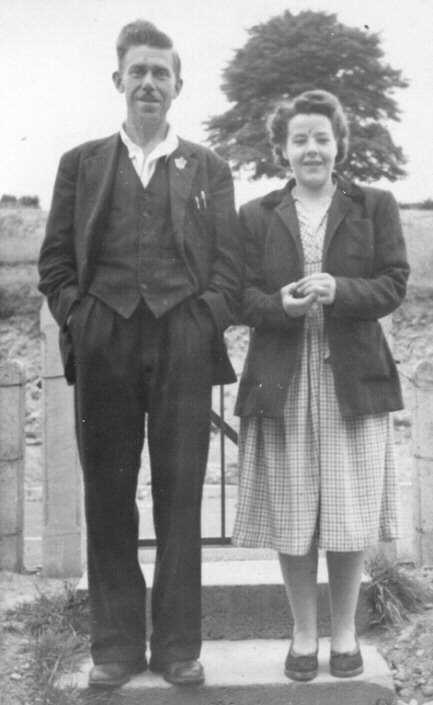

Brymbo Steelworks opened up again at the onset of World War II, and Dad went back to work there. Some of his brothers were called up for the military, but Dad - either through his motoring injuries, or through being in a 'reserved occupation' - stayed to make the steel. It was almost certainly here that he met my mother, a miner's daughter from the Moss (just over the ridge from the works). She was spending the War working on the steam-hammer in the smithy.

It would perhaps be unseemly to point out that they married in something of a hurry in February 1946 (my brother being born just over six months later), but they stuck at it and stayed married for nearly forty-three years. Not that it was easy a lot of the time. Indeed, for the first five years of their married life they weren't even living with each other. There was a dire shortage of council housing in the post-War period, and as neither of my parents had the sort of connections in the Council's housing department that enabled others to jump the queue, it was 1951 before the family was able to be together in the house in which I was born some years later.

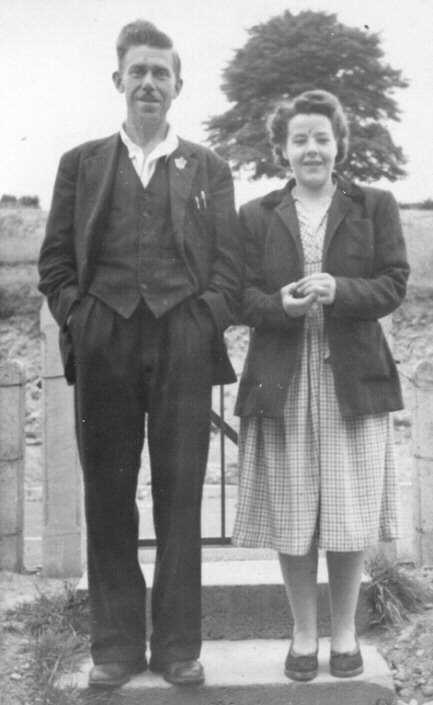

(I can't be sure, but the way my mother is holding her hands would suggest that this is either an engagement photograph or it was actually taken on their wedding day)

Instead, my father lived with his parents, my mother and brother with hers. Dad would walk the mile or so to Cerney House nearly every day to see them. I know this, because he kept a diary at around about this time, which I found after his death. I won't give any details (for one thing, I no longer have the diary - my mother presumably having thrown it out), but it was very clear that he was devoted to his family.

It may well have been a reaction to the conditions he found with his parents. It was clear to me as a child many years later that Dad, despite (or because of) being the eldest son, was not his parents' blue-eyed boy. Relations with his father (who died a couple of years before I was born) were always painted as being rather chilly, and his mother seemed to be similarly cold towards him. It was obvious throughout that Dad found his wife's family far more amiable and welcoming than his own.

Not that my parents' marriage, long as it was, was without its tensions. For one thing, it must have been very awkward only to have started living with each other after half a decade of marriage. For example (and this is a story my mother told against herself), she tended to be a bit chatty over breakfast (not a grievous fault, but an annoying one all the same), until Dad one morning cried out in despair, "For God's sake, woman, will you put a bloody sock in it first thing!". Their characters seemed to me as a child to be somewhat at odds with each other; she was very ordered and orderly, he was a bit more relaxed about things. She would plan things carefully; he would sometimes act on a whim (to her great annoyance), whether it was an impulse purchase or just going off to a football game. Money was tight for much of the time (even though Dad was a skilled worker as a burner in the steelworks), which didn't help. They would have the occasional horrendous rows which could lead to my mother storming from the house and not returning until evening. She also once threw a plate of sausages at him when he said he didn't want them.

My favourite story is another one she told against herself. My mother lived in a state of permanent mild dissatisfaction with her circumstances in life, and would often launch into a catalogue of disenchantment, telling Dad how so-and-so across the road had had a new such-and-such, how Mr-and-Mrs-Wotsit up the road had gone to such-and-such-a-place on their holidays. Dad would let the clockwork wind down and, when she had finished, gave her a meaningful look and said, "Ah, but have they got it on the table, girl?".

Domestic harmony was not assisted by the fact that my father could be the most annoying, aggravating, contrary cuss you could imagine. This he used to devastating effect on me as a child when I was trying to tell him something and he would constantly interrupt me. I suppose he thought he was trying to teach me patience; it just wound me up to screaming pitch, I'm afraid.

Anyway, my sister was born in 1955 and Dad doted on her as you would fully expect. It would be difficult for anyone to imagine, therefore, how devastating it was when she was diagnosed with leukaemia. Trips back and to to hospital in Liverpool played havoc with them all, and I don't think Dad ever got over (and why the hell should he have?) my sister dying early in 1958. It was a subject he tried never to talk about thereafter.

(I have a theory: at the time of my sister's birth, Dad was working at the Capenhurst nuclear facility near Chester. I have no proof, only a suspicion, that Christine's illness may have been connected with this).

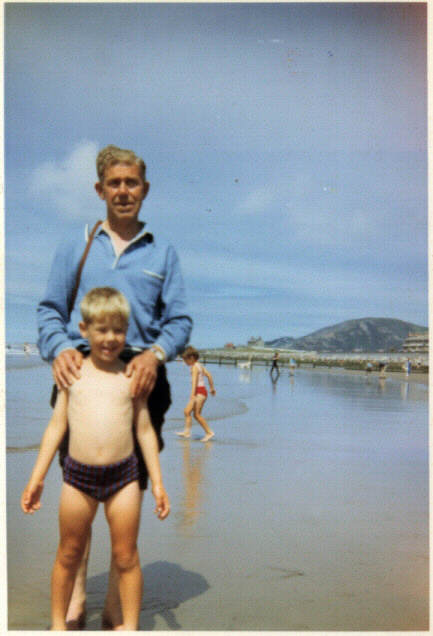

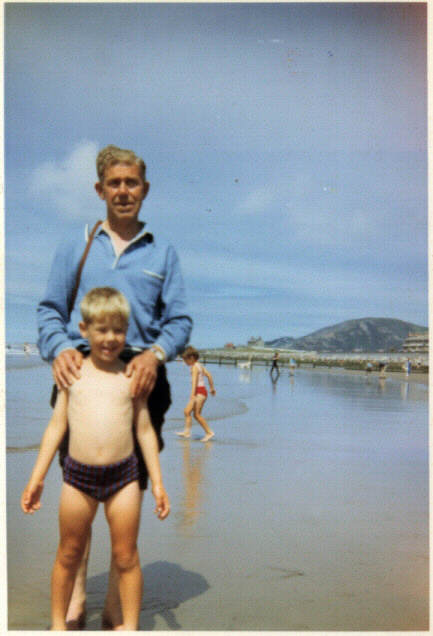

Anyway, perhaps as some perceived last throw of the dice, I was born in 1962. This meant that my father was fifty-one, my mother thirty-seven, and my brother fifteen. The effect of this from my vantage point was that I was brought up as virtually an only child (with all that often implies) and by parents who were significantly older than those of my contemporaries.

The Generation Gap™ is often bad enough without such considerations coming into play but, growing up, I always found myself feeling that whilst I was quite obviously spoiled rotten, I was at the same time subject to stricter conditions than my friends. I was indulged, but the boundaries were far more tightly drawn. This was undoubtedly true, but looking back at it all, I don't think now that that was much - if any - of a disadvantage in the long run.

I think I may have been a bit of a puzzle to my father, if not something of a disappointment in some respects. Here he was, steelworker and son of a steelworker, who had also worked in the coal mines, having a son who was a whimpering, weedy brat with no interest in the same, rugged pursuits as him; sport (I was a long time coming around to any interest in it at all), fishing (I've never to this day quite seen the point of standing up to your oxters in cold water waiting for some dumb creature to snap at a worm, especially when you could go to Macfisheries and get a nice trout for tea), and making and repairing things.

And here was his forte, by the way. He would make things; in wood, brass, whatever. He would make little tables, or brass knick-knacks (some of which I still have). He made what was famously known as The Truck, a little flat-bed hand-cart which could be used for carrying firewood, rubbish, small items of furniture, or what have you. This sturdy creation - which he made in the late Sixties - actually outlasted him. And he made a miniature version for me. He also made my go-karts. One day, I must tell you about these magnificent machines. He turned a small snooker table into a bagatelle/pinball board, and he took a wind-up gramophone, put magnets on the turntable and a plastic cover over the top, which you could put ball-bearings on and watch them whirl around as the magnets spun.

He was also extremely able at repairing things. It's difficult to get across to a lot of people below the age of, say, thirty, how important it was to be able to repair things in an age when consumer goods of various sorts were far less reliable and much more expensive to replace than they have been latterly. If you had the reputation for being able to fix a wide variety of contraptions in a satisfactory way, the whole village would beat a path to your door. Dad could fix electrical goods, clocks and watches; he could repair furniture or ornaments; and as I said, he could make things. He would seldom turn down anyone who came to him with something he might have been able to set right, and would seldom take money for it, which led my mother to warn him that he was being taken advantage of, which he probably was but didn't care very much. Doing something mattered to him, he wasn't the sort to be content with idleness.

Of all his talents, this is the one which I would have liked to possess, or at least to have in a greater degree than I do have. Oh, he could also draw a bit as well, which I envied, though this skill passed to my brother rather than me. Until the coming of the computer, I could scarcely draw a pair of curtains.

He was musical as well, and as my mother's singing was rather less than tuneful (her own father, when Mum was working in the smithy, would refer to her satirically as 'The Harmonious Blacksmith'), I'm glad I inherited what little talent - and greater love - I have for music from him rather than from her. He could play the melodion, the mouth organ and the bones, and bought a small electric organ as much for his benefit as for mine (he seldom got a look in at it as a result of it being mostly in my bedroom, and I'm sure it was only a long lack of practice which made his playing not quite up to church standard).

What the advanced age of my parents compared to those of my friends meant, however, was that in what one might call the 'cultural' sense I received a far broader and deeper upbringing than my classmates did. My parents' musical tastes were those of the Thirties and Forties rather than those of the subsequent decades. On the one hand, this meant that there was a conservatism of approach which made me seem odd to my contemporaries, but on the other side of it, it perhaps made me more broad-minded and more likely to seek out the different and the odd than they were, possibly as a reaction to those constraints.

Apart from my general weediness, he may have been rendered quizzical by the amount of time I would spend reading (a vital skill which my mother ensured I had mastered before I had even set foot in a school). He was no reader himself (although he had some books on birds, fishing and knot-tying that I remember flicking through with scant interest), confining himself mostly to the Daily Mirror when trying to figure out how to get that elusive First Dividend from Littlewoods.

None of this meant, however, that words weren't important to him. They were, but specifically in the way you could play with them, and use them subversively and surreally. This is perhaps his most important cultural legacy to me. When he would recite:

"I saw a bird upon a bough.

If he hasn't shifted, he mustn't be there."

it would give me a sort of thrill compounded with unease that something like language, which I had always taken to be a solid foundation (I was as over-ordered as my mother in that respect if in no other) could have those underpinnings mildly shaken by the most minor of twists. Add to that such nagging conundrums as:

"A man jumped over a river. Where was he when he jumped?"

to which my answer of "In the air" was met with "No, that was after he jumped", and my response of "On the ground" was countered with, "That was before he jumped" (the correct answer being, of course, "In his boots"), and you can see him trying to train my mind to deal with the world as it was, rather than what I thought it was from the things I had read. Of course, he also did it simply to annoy, stymying my frequent objections with one his favourite phrases, "Now stop your argufying and contrathraping!".

As I grew into - and through - adolescence, the conflicts between us began to emerge more obviously. More than ever I felt limited by the boundaries which had been set for me, but the possibilities of kicking against them seemed more limited still, as I lived in fear of the flat of Dad's hand nearly as much as I feared my mother's international-standard sulks when I had crossed her. Let me set it straight, in case there should be any doubt in your mind, dear reader: my father was no brute; in fact, he was a very even-tempered man except when those standards he felt were sacrosanct had been breached. He didn't have to hit me - or threaten it - very often; as I said, I was a wimp (a "babby doll", as he would call me in exasperation), and feared punishment at home as I did in school. It was an old-fashioned approach, as one would expect from someone who had been brought up either side of The Great War, and I don't reproach him for it, really.

But this is no moment for settling old scores, real or imaginary. There are other, more worthwhile things to remember about him. His withering opinion of the pop stars of the late Sixties for example, summed up in his frequent complaint, "You hear them singing, "I Love You, I Love You, I Love You!", and there it is in the papers the next week: "Divorce!"!". Or his weary sigh when the newspaper or television news had brought fresh evidence of Man's inhumanity to Man, "What's the matter with people, I say?".

He was a teetotaller, and had been ever since a bad experience with farmyard cider as a young man, and it was always amusing to watch the fight he put up against having a small glass of port and lemonade to see the New Year in. He always gave in, but that was as far as it went for him. This did not stop him, when I was about fourteen or fifteen, from bringing back small cans of lager from retirement presentations he'd been to, and handing them to me with the solemnity of a tribal elder administering some rite de passage. I only learned my lesson at the age of nineteen, and white rum was to be my downfall.

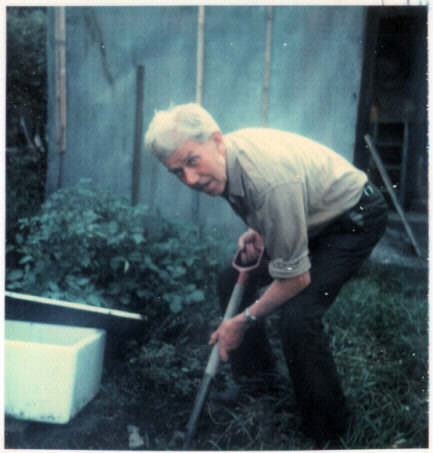

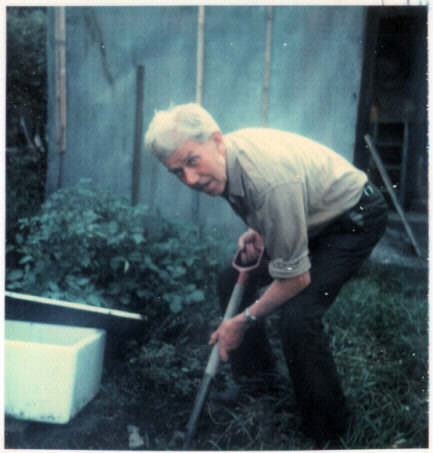

There was his love of walking. Even when he was in his late sixties and retired, he would walk the four miles into Wrexham just for something to do, and would frequently walk all the way back as well. This was a continuation of an old habit: he had become involved with Brymbo Steelworks Football Club shortly after it had been founded in the Forties (he ended up as a Life Member), and was known to walk ridiculous distances to watch away games. To Ruthin, for example, a distance of some fifteen miles. More than that, people he knew would stop their cars and offer him a lift, which he would cheerfully refuse, much to his acquaintances' bemusement. I can't say that I could ever equal his distance record (I think I got up to six and a half miles once), although I too used to do daft things simply to follow the team (I finally got interested in sport - as a spectator only - when I was about twelve, and I was helping to run the Club by the time I was nineteen).

There are so many other things I could have told you but can't, either because I'm not clear on them, or because I never asked. He was a fund of anecdotes, and what he told me may have been somewhat embroidered (I refuse to concede even the possibility that he was making them up).

For by the time I had got the stage where I was interested enough to ask him more about his life, he was in no real state to be of help to my curiosity. As he neared his seventieth birthday, he was struck down by a condition of the inner ear - perhaps some delayed further effect of his encounter-at-speed with the post box all those years before - which caused him to suffer from a sort of permanent mal de mer. For one who had been so fit to suffer such a fate was unseemly, unfitting and grotesquely unjust. He also became almost totally deaf, which rendered any sort of communication with him difficult.

I will draw a veil over his final years, save to say that seeing him plunged into a state of near-permanent gloom with his self-confidence stripped away from him made me inwardly scream with rage to the very heavens, and may well have crystallised my view that - if there were any gods - they had an attitude which was scarcely more elevated that that of a malevolent, maladjusted child. He died just over a week after his seventy-eighth birthday in December 1988.

I look back on what I've written, and - not for the first time - I find myself unsure of what the hell it was that I wanted to say. Was it to try to explain to myself how I came to be how I am, and what Dad's part in that may have been? Possibly, but I'm not at all sure what it might be about me which reflects upon - or has echoes of - him. I look in the mirror, and I can't really tell whether I look like one of Dad's family, or like one of the male members of my mother's. Sometimes I think the one, sometimes the other. Temperamentally, I feel the inheritance is just as split, as I suppose it was always likely to be, so no revelations are forthcoming there. Perhaps it would be for someone who knew him and who knows me to be the judge of it. If so, I'd be grateful if they kept it to themselves.

No, perhaps the whole, the sole reason for writing all of this is to mark something of the life of a man who, whilst never famous, was remembered well by all who knew him; a man who, although of lowly status in the world, could be as noble as any wise man or potentate; and a man who, for all his faults, tried to do the right thing as often as possible and help other people when he could. And those aren't things which should ever pass from memory.

Or perhaps I just wanted to say, "Happy birthday, Dad".

File under: Me

This Is Not A

BLOG!

This Is Not A

BLOG!