This Is Not A

BLOG!

This Is Not A

BLOG!

Date: 04/11/24

ISM-ism

I hadn't really wanted to write about this, but this piece by Hugh Muir in the Guardian on Monday has forced me into an embarrassing admission.

(As an aside, why do Brit Libs seem to assume that only the non-white sections of the population are pissed off with all the Empire nostalgia which appears to be the only thing holding up the UKanian state? There are plenty of us melanin-challenged folks who view such exudations with similar, if not greater, distaste).

Anyway, to begin somewhere near the beginning...

Way back in the when, it was the custom of the Depratment to present certificates to its corps of slaves upon their reaching twenty-five years of meritorious service (they didn't always get it right, as I describe here). Once Human Resources was centralised, this practice ceased, presumably because the new, thrusting, go-getting 'People Function' (as it was re-named briefly, though nowhere briefly enough) thought that it was sufficiently incentivising that we be paid every month.

Wind forward a bit: it's February 2020, and about a hundred and fifty of us are coming up for redundancy as a result of our office being closed. We each had to have a one-to-one discussion with our line manager as to whether we intended transferring to Liverpool or Telford, or move equally laterally to a different part of the Civil Service forest, or simply to take the money and run.

During my chat with Julie, she mentioned that she was nominating me for an award. I was suitably flattered for a moment, before she told me that the 'award' was something called the 'Imperial Service Medal'. I instantly demurred because of that one word 'Imperial', regarding such a description as a pathetic joke (had it been called, say, the 'Public Service Medal', I would have had no problem with it). Nonetheless, Julie sent the nomination form off and that was that.

Four and a half years then went by, as they tend to if you hang around a bit. My hope - when I thought about the thing at all, which comes under the heading of 'seldom' - was that they had either not approved the application, considering me to be have been too much of a subversive for such an accolade (which would have delighted me to the max, although my talent for disruption had long since been overtaken by that of the Depratment's senior management), or that they had forgotten altogether.

Back in July, I returned home from my Wednesday social to find one of those Royal Mail cards shoved through the letterbox. Postie had, it seems, tried to deliver a parcel and - it presumably having to be signed for - was unable swiftly to complete his appointed round (missing signatures seemingly out-ranking snow, rain and gloom of night). The card gave a reference number for me to input on the website of Royal Mail (by appointment to private equity). If I didn't tell them otherwise, they would try to deliver again on the Thursday. This was a potential problem, because I had another heavy dental appointment on the Thursday morning, and I was unsure as to whether I would be home in time.

In trying to arrange the delivery for Friday instead, I tried inputting the serial number on the card, only to find that it wouldn't accept it. The main difficulty was that the final character of the reference was unclear; was it a '7'? A '4'? An 'H'? It was no-go in any case.

I then spent the rest of the day pondering who would have sent me a parcel. I hadn't ordered anything. Perhaps it was my dear friend Siān sending me a book (perhaps even one of her own?). Mystery...

On Thursday, I managed to get back from my ordeal before noon, and so was present when the knock on the door came shortly afterwards. There stood Postie with...a padded envelope. Perhaps I'm old-fashioned, but I would never regard an A4-sized envelope as being in any true sense a 'parcel'. Anyway, I signed for it and took it in to the living room.

In that anticipatory way which one learns at childhood Christmases, I felt around the package. There seemed to be something hard and rectangular within. Finally, I opened the envelope and found another envelope (white, unpadded) inside, plus the rectangular object within a thin card slipcase. Sliding the item out, I found it to be a red case of that type which might contain either a high-end ballpoint pen or a large tie-clip. Opening it, I found...this:

Damn! They had caught up with me after all!

I opened the white envelope to find it contained:

- A letter from someone called the 'Departmental Honours Secretary' who was, at least for the purposes of protocol, 'pleased' to enclose my Imperial Service Medal.

- A certificate from the 'Registrar of the Imperial Service Order' written in florid script with equally florid language ("I am commanded...Her Majesty The Queen has been graciously pleased to award to you...I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant"). The signature could have been Lupine Wonse for all I could ascertain.

- A small piece of paper telling me that my new 'honour' had an insurance replacement value of £70 (this was signed by the same functionary, but this signature made it clear that my correspondent's forename was 'Stephen' and that he appeared to be not merely the Registrar but also the Secretary of the 'Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood'. I'm sure that he felt he was slumming it a bit in my case.

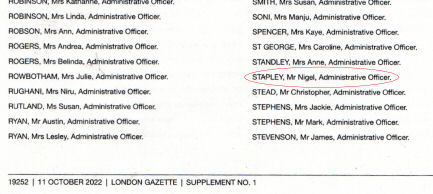

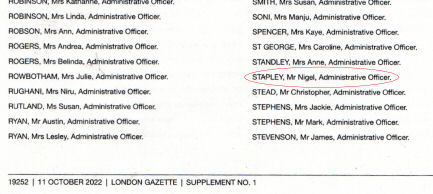

- A photocopy of the relevant section of the London Gazette for 10 October 2022, as seen below:

(Yes. 2022. As the covering letter explained, the pandemic (remember that, chums? Don't worry if you've forgotten; there'll be another one along soon) had brought the minting of medals to a halt, and they were working their way through the backlog. This also explains the references to Lizzie Two, and the thought occurred to me that my accolade may have been one of the last which she was 'graciously pleased' about. Indeed, it may have been the trigger for her demise. This wouldn't have been the first time that a Stapley had done for an English monarch; a very distant relative - 'distant' as in 'back several generations and over to one side a bit' - was one of the signatories to the death warrant on Charles I. Don't say that our family has served no useful purpose to the world).

On detailed examination, I saw that nearly all of my colleagues of my own grade or below were listed (providing they had done their quarter-century of slog, of course). It was uncomfortably like reading one of those village war memorials.

I sat there with the medal in my hand. Turning it over, I saw the engraving of a figure from classical imagery, a naked man (with a strategically-placed thigh preventing the image from being seizable), apparently resting from his labours, with the legend 'FOR FAITHFUL SERVICE' under his left foot. "That's what they thought", I murmured. My name was also engraved on the edge of the coin, which removed any potential re-sale value, even for £70.

I chuckled. I mean, what else could I do? It wasn't as if I was going to send it back. For one thing, I wasn't going to pay for its return; and, for another, I was willing to curb my annoyance at my having been successfully bought after all with the thought that keeping it would constitute an ironic act on my part.

Well, that's my excuse anyway.

This Is Not A

BLOG!

This Is Not A

BLOG!