The Judge RANTS!

The Judge RANTS!

Date: 04/11/10

Twenty Empty Years

This week marks the twentieth anniversary of the closure of Brymbo Steelworks, with the direct loss of over a thousand jobs and the indirect loss of hundreds more in the area.

It is difficult to express to those who have not grown up in such an environment how great a part a steelworks (or a coal mine, or a shipyard) can play in the lives of those who live cheek-by-jowl with it, even if they themselves have no direct connection to that industry. Because such an industry creates more industry around it, provides jobs (and therefore some hope for continuity) and forges (if you'll excuse the pun) a sense of community solidarity which no amount of half-arsed 'initiatives' from local or central government can ever hope to replicate or create out of the deserts of despair that so many such areas have become during my lifetime.

In my own case, and in the case of my parents', grandparents' and great-grandparents' generations, the steelworks had always been there. Sometimes prospering, sometimes less so (and during The Great Depression, closing altogether for a time), but at all times a symbol of some core of our identity.

It had been founded by the mad Iron King himself, John Wilkinson, in the late eighteenth century, and located to make the best use of the local coal and limestone deposits. It had gradually expanded until, in my boyhood, it had taken over a substantial area of land on the south-eastern edge of Brymbo.

My paternal great-grandfather, Alfred Stapley, had come up from the Hastings area at the tail end of the nineteenth century to work there, and had brought most of his large brood with him. One of the sons, Harry, had joined his father at the steelworks by the time he was about fourteen. In turn, a number of his sons went on to work there, including my father, although economic circumstances forced him to work elsewhere for periods in the thirties through to the mid-fifties. By the time he retired in 1975, my old man had spent thirty-five of his fifty working years in 'the works'.

Although I never continued the tradition, in that I was foolish enough to get myself over-educated and therefore useless for any real work, because of the family connections and because of its dominant position the works nevertheless played a huge part in my life from its very beginning.

When I say that the works had a dominant position, I don't necessarily mean in the sense that it towered - or even loomed - over our homes in the way that, say, the shipyards of the Tyne and the Clyde did. In fact, quite the opposite, because the steelworks stood below our homes up here on the Penygraig estate; an estate which had been built in stages between the nineteen-twenties and nineteen-sixties largely to house people who worked in and around the works.

The council house in which I was born, and where I lived until I was nearly twenty-two, had two bedrooms. Mine, the smaller of the two, was at the back of the house facing slightly north of east. Within the field of vision from the window was the larger part of the steelworks complex prior to its expansion southwards in the late seventies. This meant that in all weathers other than the thickest fog the works could be seen - and heard. On summer nights in particular - in the times when we used to have summers where this was necessary - the open window would bring the sounds of heavy industry into my bedroom; the clanking of the shunting wagons, the hissing of steam escaping, the sonic background radiation of our lives.

(Such was their dire condition that the same windows when closed would still admit the same noises all the year round with little diminution of volume).

This might sound like some sort of sonic dystopia (I remember the great John Peel describing trying to sleep in the spare room of his mother's house - which stood next to railway sidings - as "trying to sleep through a concert by Einstürzende Neubauten"), but it didn't seem in any way intruding; or perhaps it was simply that we were used to it, and only the annual maintenance shutdown in late July/early August each year seemed eerie as all normal noise ceased.

I've sometimes had cause to wonder whether this subliminal soundtrack to my childhood conditioned me for a partiality to certain types of music later in my life, rather in the same way as the somewhat sinister hum from the electricity substation by Pinfold may have led me to a taste for electronic music. We are all influenced by our upbringings in ways which - if they ever become clear at all - only become discernible with hindsight.

It wasn't just the sounds, however. A steelworks - especially in the days before a stronger degree of environmental awareness became prevalent - also produces other things; smoke and dust and the general tang of hot metal in the air. The smoke itself wasn't too much of a problem for us up on Penygraig, as the prevailing winds seldom blew it our way, but the dust was a different matter. Being heavier, it had a tendency to seep across and up from the valley in which the works stood, and windows when cleaned didn't tend to stay clean for long. The effects of the dust - and of the fact that most houses in the village at that time still had coal fires - could be most clearly seen on the sandstone buildings in the bottom half of the village, directly due north of the steelworks. The village primary school, some of the chapels, many of the houses; all had been turned black by the dust and soot.

Much of the dust was so fine as to render it invisible in normal conditions, but it nonetheless lent a certain faint haziness to the air, particularly in warm weather. It's odd the things one can be nostalgic for; I have a particular view in my mind (perhaps a composite recollection of all the times I did this) of standing on the old bridge on Railway Road on a still July afternoon, looking across at the tree-covered slope on the Brynmalley side of the valley with the very slightest haze like a very fine gauze hanging in the air.

Of course, what this was all doing to our health could only be imagined, although I don't remember any widespread incidence of respiratory conditions amongst my schoolmates at that time.

There were other ways in which the steelworks' existence impinged on every aspect of our lives. The work which it created meant that this village - with a population of some two and a half thousand at that time - had six pubs (The Miners' Arms, The Furnace, The Railway, The Black Lion, The George And Dragon, The Mount Hotel), a Conservative Club and a thriving British Legion branch; shops (Sooty's on Offa Street; Bloor's on Penygraig Road; Pryce Davies' (Gwalia Stores), Bert Evans' paper shop and a large and diverse Co-op (all on High Street); Sims' paper shop on Coedyfelin Road; Colenso's on Railway Road; Vera's on Harwd Road. This in addition to a chemist's and the Post Office (also on High Street), two butchers' shops (one on Harwd Road, one on Ael Y Bryn), at least three hairdressers/barbers, and two chippies.

There were other things, too. The sight of the diesel locomotives shunting up and down the line past the school, and the old-style, heavy-wooden-gate level crossings at Brymbo East, Middle and West, complete with their signal boxes. Similarly, seeing the yellow shunting engines going up and down the line which ran alongside Blast Road.

The steelworks was also, of course, one of the hubs of our social lives, along with the British Legion, the chapels and churches and the pubs (if you were of an age). The steelworks had its own Social and Sports Club, although this was located on the farther side of the works from us; practically in Tanyfron in fact, and reachable from Brymbo only by means of a winding country lane (up which unsuspecting lorry drivers were sent - or sent themselves - from time to time with - as they say on television - hilarious consequences). If you had the authority - or the cheek - you could of course just cut straight through the works itself and save yourself a mile.

The Club had its clubhouse and a variety of sporting sections; darts, snooker, tennis, bowls, cricket. And of course football. Brymbo Steelworks Football Club - although founded as late as 1946 - had developed an enormous reputation as one of the top amateur clubs in the whole of Wales. My father had been an early stalwart of the club, a connection which continued for the rest of his life, and which passed down to me and my brother as we spent several years in the eighties helping to run the club. It was inevitable, then, that he should start dragging me along with him on a Saturday afternoon to The Cricket Field ('The Crick'). I can't say that at the age of four or five I was at all interested in the game; it was just a way of getting me out of my mother's hair for a couple of hours. At least we seldom had to walk the long way round; everyone knew Bill Stapley, and no-one would have questioned his presence walking his small son alongside the shunting lines and past the stacked billets and ingots.

Following the football brought its adventures to me even at that age. I well remember one trip - either for a pre-season friendly or for a Welsh Cup game, I forget which - to Ellesmere Port, which might as well have been Samarkand such was the distance to my four-year-old mind. After the game (which we won 5-0, my father winding up a home fan by telling him that, next time, we were going to bring the first team) we headed off to some sort of club, which may have been in Chester. Wherever it was, it was deemed out of bounds to me and so Dad and me went back and sat in the bus for about three hours until everybody else returned, piling me with chocolate as recompense. On the way home, we came back up through the road tunnel which ran from The Lodge under the main part of the works and which brought us to High Street, from which we walked the remaining couple of hundred of yards home. We arrived back at about half past midnight, and Mam didn't half give my old man Down The Banks. No harm done, though, as he himself patiently pointed out, though it didn't stop her from referring to me jokingly as a "dirty stopout" for weeks afterwards.

As far as the viability of the steelworks itself was concerned, apart from that period in the nineteen thirties when it had been mothballed (a policy which was quickly reversed as war loomed; indeed my mother worked in the smithy there during hostilities) the place had never run at a loss. This is all the more remarkable given what happened in the post-war years when, depending on the policies adopted by the government of the day, the works moved from private ownership to nationalised status and back again two or three times. This didn't seem seriously to affect the prospects for the place; indeed, the mid to late nineteen seventies saw a major expansion southwards, with a new rolling mill and its attendant railway sidings wiping out the old Crick.

The works was back in private ownership by this time, with GKN having once more taken over from British Steel. Public or private, however, we sensed that tougher times were ahead with the coming of a government in London determined to pursue a hard-line ideology which held that large-scale unemployment was a price worth paying for what they termed 'efficiency', and which believed that, whatever the costs to those who were not of their class, the heavy industries of the UK and the sense of solidarity and collective power which went with them had to be crushed in order to usher the land into the neo-Golden Age where high finance and the 'service economy' were to dominate our lives.

Nonetheless, despite frequent alarums and excursions, Brymbo Steelworks survived pretty well in the first half of the eighties, albeit with falling numbers of staff. But the graffiti was on the wall, in the form of a new company set up as a joint venture between GKN and British Steel, to be called United Engineering Steels (UES). This new company would have control over the output of Brymbo and of a number of other steel plants - mostly in Yorkshire - which were concerned with the production of high-quality steel for specialised use in the automotive and other industries. The company's headquarters would be in Rotherham, which should have given us a fair warning of what was likely to await us.

The signs were not good when UES claimed that it couldn't afford to install new technology to reduce emissions from the works. This had come in the wake of people on a new housing estate across the valley in Pentre Broughton complaining about the dust which would drift across to them. They - many of whom were not from the immediate area - were agitated about the pollution reducing their ability to cash in at the height of the next property bubble.

UES invested virtually nothing in Brymbo in the next four years, concentrating instead on their Yorkshire plants which used the 'continuous casting' method which - in tune with the spirit of the age - produced far higher quantities of steel, but at a lower overall quality.

Perhaps, then, we shouldn't have been surprised to be told one morning in May 1990 that UES had decided to close Brymbo, with the loss of over twelve hundred jobs in the works itself, and doubtless many hundreds beyond her gates. The announcement had been made to a press conference by the chairman of UES, one John Pennington, before Brymbo's workers had been told, such was the regard in which the workers - who had been optimistic and confident about the plant's future - were held by the company's senior management.

All hell broke loose: Wales' TV cameras and the radio reporters - who had thought the whole area scarcely worthy of note during the previous decade, concentrating instead on the daily disasters of de-industrialisation in the southern valleys - descended; workers and residents were importuned for their opinions; the politicians had their shout.

After the initial shock, a campaign began to grow. The local MP, John Marek, secured an Opposition Day debate in the House of Commons. Neighbouring Labour MPs joined on. The local councils at County, Borough and Community level came together to try to bring pressure on the Secretary of State, David Hunt, to get UES either to reconsider the closure plan or to allow the sale of the works as a going concern. After all, it was pointed out, if Brymbo was not competitive (as UES claimed), then what harm could come to UES by allowing another company to take it over? And, if they actually feared competition from it, what excuse could they have for closing it?

Public meetings were held, politicians were lobbied, leaflets, badges and special newsletters were distributed. Even in an area justifiably renowned as Europe's Permanent Capital of Apathy, actions and emotions were stirred.

As could have been predicted by anyone with any degree of connection with reality however, there was to be no reversal of UES' actions. After all, it had got all that it had wanted; the order books, which were duly dispatched to Rotherham to be fulfilled by continuous casting. The bitter irony that the first batches of steel made by that process after Brymbo closed were returned by the shipload by customers unhappy at the drop in quality was scarcely any consolation to us.

The people and the politicians had once again proved impotent in the face of the power of big business to arrange the world for its own convenience and no-one else's. David Hunt proved as powerless as all the rest of us; reduced to bleating that he had tried his best, but that you couldn't buck the market.

The last steel was made in September 1990 and by early November it was all over, and the gates closed on two centuries of quality steel making.

A cold, malignant gloom settled on the site and, equally, on those of us who lived around it. UES sold off the furnaces, the burning hearts of the steel business, to China. There was to be no going back.

Nor was there to be any going forward.

For if anyone was sufficiently starry-eyed to believe that we could clamber back to our feet, regroup and move on to new success with some other use for the site, they had reckoned without the cupidity of developers, the hand-wringing incompetence of the local council, the scarcely-feigned indifference of the Welsh Development Agency and similar quangos, and the powerlessness of our Members of Parliament.

For this was the time of one of the numerous economic recessions deliberately engineered by those who held high political and economic power; recessions which were explicitly designed to enable the financial sector to get what it wanted, irrespective of the damage such policies would do - and had already done - to the lives and prospects of millions. In the Wrexham area over the previous decade or so, we had seen the end of the coal industry, the brewing industry was being 'consolidated' into larger (or perhaps that should be 'lager') corporations with their interests a long, long way away, and now the last heavy industry in the area was being wiped out in the name of 'the bottom line'.

The site of Brymbo Steelworks lay idle and unregarded. The fate of those left behind quickly slipped off the media and political radar. The next time that the site made the news was when an abortive attempt was made to demolish Electric Melting Shop (EMS) No. 2 (the place where my father had worked during the years leading up to his retirement). Despite having being told that geligniting the structure was not a good idea, the contractors went ahead and did it anyway, presumably because one of them had a piece of paper tellling him how clever he was. The only result was to blow the metal panels off the sides, twist the metal supports (thus rendering the whole edifice unsafe) and send a huge cloud of metal dust into the air where, five hours after the explosion, you could still taste it.

The aftermath of the failed attempt to demolish EMS 2 in 1993

The next step was the announced intention to shift large amounts of toxic waste from the site, supposedly to enable redevelopment. Friends Of The Earth research showed that the waste contained high levels of heavy metal contaminants, dioxins and PCBs and was therefore not safe to be disturbed.

Year after year, nothing was done. Virtually uniquely in the British Isles, Brymbo remained (and remains) the only former steelworking site not to have been completely redeveloped.

The redevelopment of the site was placed in the hands of a company called Brymbo Developments. However, despite its local name, the company was a newly-established front for a firm completely owned by three businessmen from south-east Shropshire. They were given almost total control over the site and what was left on it.

After the EMS fiasco and the plans to move lethal substances through one or more densely populated villages came the real meat of the plans as far as the developers were concerned. For this was the age of the Property Bubble™, and housing was a huge area for profit. And so Brymbo Developments - after a few years' further delay - finally stated their intentions. They wished to build a large number of houses and blocks of flats - sorry, 'apartments' - on the southern end of the site. By means of this, they claimed, they could raise the money for their rest of their plans (which were probably called 'exciting' and 'ambitious', as is customary on such occasions); the parade of shops, the small industrial units, the new road which would link the new development with the old village (the only existing roads going all around the houses - literally - to get there).

The number of houses/'apartments' varied from time to time. Was it three hundred or five hundred? Or six hundred and fifty? Whatever the number, there was yet more delay. It wasn't until 2005 - a full decade and a half after the steelworks closed - that any serious work was done to prepare the site for its new purpose.

There was a lot of work to be done, and the developers went to it to clear the southern end of the site for their much-vaunted housing project. There was much more to do to the site than that, such as major landscaping work to lower or remove the huge banks upon which the steelworks expansion had been built. Not that the developers had to worry too much about such a large-scale enterprise eating into their profits; by one of those nice little arrangements, most of the landscaping at the eastern edge of the site was done with public money.

New houses being built on the site of the old rolling mill, 2005

Landscaping work on the old steelworks bank, 2007

It might be considered a misfortune that all the new properties at the Tanyfron end of the site became available for sale just as the hyper-inflated property boom of the early years of this century went "Pffftt!". If so, then that misfortune was not shared out very equitably (it may have been a dry run for The Big Society). While the money from selling the properties - which, we were told, was to be used to provide all the other amenities and segments of the development - failed to materialise, the developers paid their shareholders nearly £15million in dividends in just one year. And then had the nerve to demand that public money be used to pay for the so-called 'Spine Road' to the old village, even to the point of refusing to sign an agreement stating that no more housing was to be built on the site before the road was in place. And that is in addition to wanting (and getting) planning permission to put even more houses on a playing field on the edge of the Penygraig estate.

The local politicians have, with notably few exceptions, done everything they can to accomodate the developers, even if that meant acting against the longer-term interests of the people they were supposed to be representing. The 'national' politicians, at Westminster and, latterly, in Cardiff Bay, have done little other than to drag themselves up here from time to time to do a bit of tut-tutting for the media and then piddled off back to their cosy little bubble. The development agencies have been comatose, although this has not stopped them from pulling out all the stops to redevelop other sites of heavy industry; when Ebbw Vale steelworks was closed a few years later, the site was revamped and up-and-running within about three years. And CADW, the public body which is charged with protecting our heritage and monuments, and whom - one would like to think - would be concerned with preserving the oldest buildings on the site which stretch back to the nineteenth century, has shown such a foot-dragging lack of zeal that those historical structures are now literally falling down by the day.

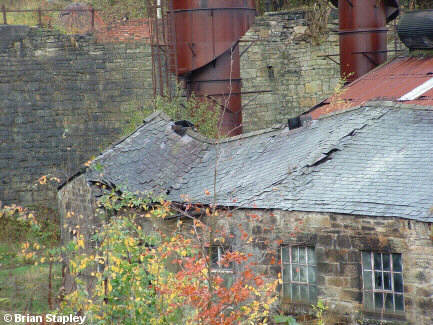

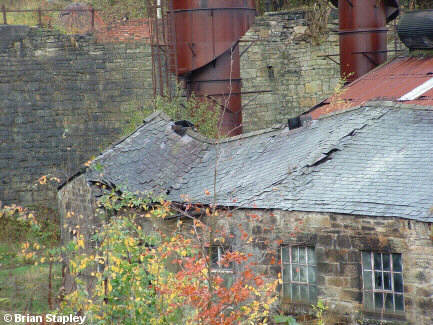

The old carpenters' shop, Brymbo Steelworks, early 2010. The roof has since collapsed completely.

What do we have to show for it all after twenty years, then?

- A site which is still largely derelict, with even the historic buildings at the northern end of the site left to fall apart through the apathy of the quango which is supposed to be concerned with such things

- a few hundred houses and 'apartments' which the developers can't get shot of

- no small industrial units

- no shops

- no road linking the site with the existing villages

- And no jobs. Not a one. Once the residential properties had gone up, that was it on the employment front.

No jobs. With all that that entails for the communities which had been founded on - and sustained by - skilled labour. We have seen the inevitable social consequences of the slash-and-burn approach to industry and the economy, an approach which benefits asset-strippers such as UES and property speculators such as Brymbo Developments, but which is willing to discard human beings and the communities in which they have their being.

The knock-on effects of the closure for local business have been equally devastating. Since 1990, three pubs, the Legion and all bar one of the general stores have closed. A village of some three thousand people has been left with little more than the Post Office (currently up for sale) and the chemist. Efforts to attract small businesses in - or to encourage the development of them from scratch - have failed. The building of a so-called 'Enterprise Centre' on the Blast Road (to replace a Community Centre which was forced to close because the county council couldn't be bothered to maintain it) has created nothing more than an internet café and a crèche.

We are now into the second generation of families which have never known steady, reasonably-paid employment and - whilst I wouldn't claim that we have become Dodge City, especially as there are villages nearby which far more credibly fit the description - alcohol and drug use amongst the young - and anti-social behaviour from them and from those who in other circumstances would be deemed old enough to know better - has increased markedly. A sort of numbness settled over a place which already relied heavily on a sort of dumb apathy for its modus operandi.

**********

I've spent four or five days writing this piece, and I'm still not sure what it is I want to say. Except perhaps this: when a country is so arranged that the people become subservient to the needs of The Economy, rather than the economy arranged so as to put people and their needs first, you will end up with a society (if such it can still be called) which is riven by lumpen hopelessness, split by unnecessary inequalities, mutual suspicion and even open hatred, and is, indeed, Broken.

And that that state of affairs is deemed to be not only the norm, but even desirable by those who own and control our world, is a symptom of a coarsening and deadening of our common humanity.

I suppose I'm still just plain fucking angry at what was done to us twenty years ago this week. And I hope I always will be.

The Judge RANTS!

The Judge RANTS!